How to use Scrivener for worldbuilding–and a lot of other things, incidentally–is the first in a line of what I’ll call “The Basics.” Generally, what I’m interested in writing about is a bit farther down the line of writing craft, but if somebody new to writing visits my blog, I want to have articles to point them to, and which I can also build on later with posts like “Characterization in the Luna Books,” or “How Tolkien Built a World on Linguistics.” (The latter is going a bit far for me. In fact, I’d much rather just discuss his history-making.)

Long story short, if you already use Scrivener, you may not find anything new in this post. If you don’t already use the program, or are simply new to writing and unsure how to approach this worldbuilding nonsense, maybe this post will be of some help to you. I’m a chronic pantser, so I’m not going to give you plotting tips, but I can tell you how I keep track of all the shit I come up with on the fly as I’m writing, and how that eventually makes a cohesive file on a new world!

Worst case: after this you’ll know what not to do, ever, when writing.

Onward!

The Actual Basics: What is Scrivener?

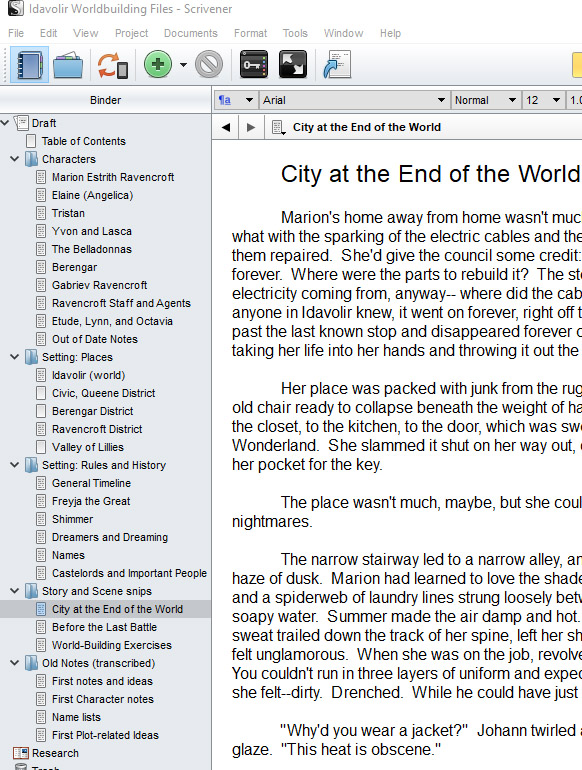

Scrivener is basically a word processing program. Compared to Word, it has limited text-formatting capability, but it comes with other features that can be invaluable for drafting fiction or, in my case, organizing worldbuilding notes. It has a corkboard view, allows you to split the screen between different parts of the file so you can view documents side-by-side, and by default the program displays your entire document in an outline on the sidebar, among other things. The program is pretty flexible. I have used it to compose a rough story draft before, but I actually prefer using it for organizing my notes, so this post is going to be biased in that direction.

The program comes with a thorough tutorial, so I’m not going to cover stuff like what each template does and so forth. For worldbuilding, we create a blank one. However, I will outline some of the program’s functionality as part of my guide.

Why use Scrivener instead of Word/etc.?

So, why use Scrivener instead of Word or Google Docs? Good question! After all, Word has stronger text-styling options, and Google Docs isn’t too far behind. (I have never used Open Office, so I can’t comment on it.) Scrivener can do most of the formatting you might want while drafting a story, but when using it for worldbuilding notes, I personally run into a few problems. For example:

- It doesn’t have a ton of flexibility when formatting lists. Scrivener is stubborn about sticking to its presets.

- Scrivener does not give me as many presets for text blocks as I would like. It has the basics–it has enough. Just not always what I want.

- Inserting and resizing images is easy enough, but the text will not wrap, nor allow any convenient formatting.

On the other hand, Scrivener allows me to see my entire world at a glance.

If I need to find my character notes for Gabriev or the history I came up with for Freyja’s conquest, I don’t have to scroll or worry about setting up a functional table of contents. As you’ll see later, if I want to view two different pages at once, I can do that via split screen.

I’m sure Word has some functionality I’m missing. Thing is, Word is clunky as hell, and Scrivener is quick, at least on my computer. Or… maybe I’m just being ornery. But it’s great for organizing my messy notes, and it auto-saves frequently, which means I don’t often lose my progress. I’m hooked.

Worldbuilding: Create Your Scrivener Template

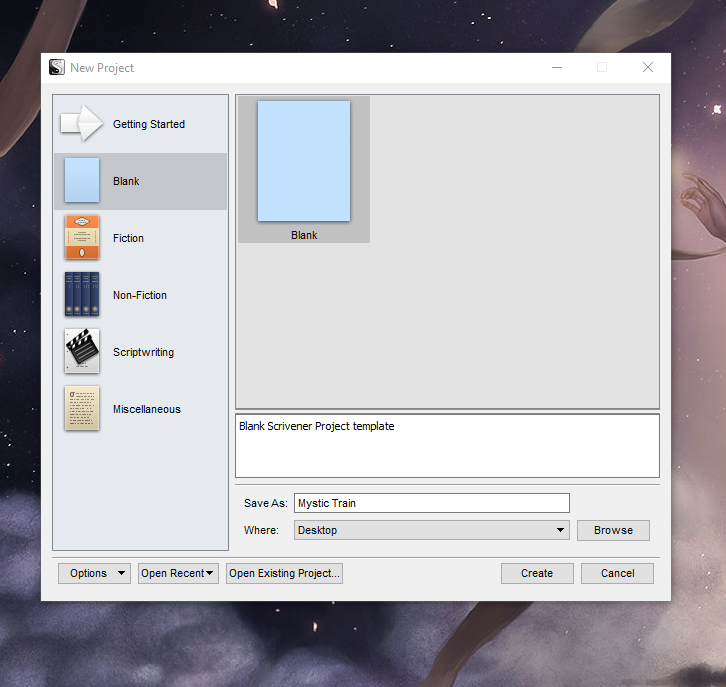

Scrivener has you create a project, not just a file. This project will encompass dozens of files related to your story, so it helps to have a working title and some idea of what you need to build. I personally use the following steps

Brainstorm a Title: come up with something to call the story or world. This could be a real story title, or just your shorthand name for the world. Ages ago I toyed with a story idea that has basically already been done now in Under the Pendulum Sun, but the centerpiece of the story was a train. I call the world “Mystic Train,” even though that’s definitely not going to be what I call the story. So if you have a story you want to tell, just name it something that’s gonna stick with you. If that means you’ve got a story about your parents’ dysfunctional relationship, and all you can think of to call it is “Deadbeat Duo,” then do it. Whatever works!

Create the File: as a rule, I always choose a blank template. Scrivener has presets for different sorts of writing, which can be helpful for structuring your file if you plan to compile a formal submission with the program. I don’t need them for worldbuilding notes, however.

Choose where you want the file to go, and hit “Create.”

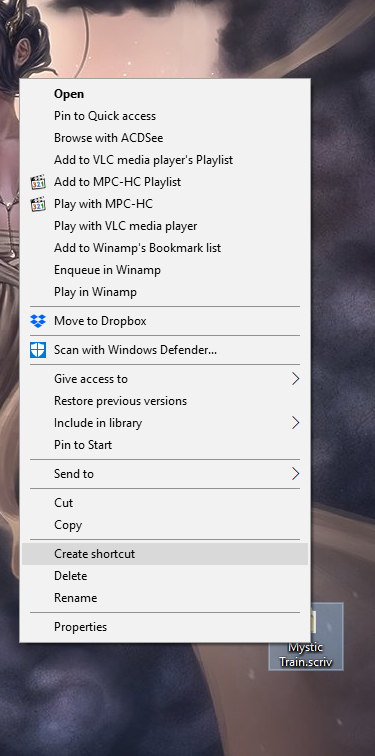

Make a Shortcut: if you like having easy access to your files on the Desktop, find the .scriv file and right-click. You should see an option to create a shortcut, and then you can move that wherever is easiest for you.

Worldbuilding: Basic Categories

Keep in mind that I primarily write fantasy, with some dabbling in science fiction. I’ll go into how worldbuilding is useful for literary fiction in some other entry, but spoiler: it’s not irrelevant.

Now, let’s divide our newly-made template into appropriate categories.

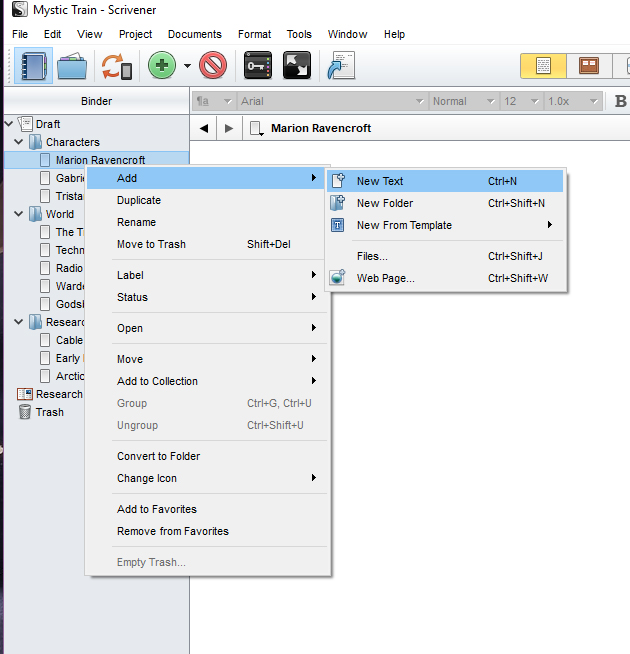

Using Mystic Train as an example, I created three catch-all folders to start: characters, world, and research. (Yes, there is already a “Research” folder in there, and I use it for a specific purpose. More on that below.) Every time you need a new page, just right-click on the category and choose your file type.

Worldbuilding pages you might want to begin with:

- Characters

- Your major characters, like the point-of-view character, their significant other or best friend, etc., the antagonist/villain

- Any important side characters that your mains talk to a lot, and/or capricious gods that influence the fate of your story (if they’re directly involved)

- World and/or history details

- Did some major event happen in the far/recent past? I write fantasy, so let’s talk about cataclysmic wars. That’d be a memorable event that your character should at least know about, even if they weren’t present.

- Government: Who rules right now? What kind of government is it? Even a tiny detail like “they live in an oligarchy” provides guidance when your character needs to complain about taxes or something.

- Religion. Is there religion? You should have notes on that. Think of the opportunities for swearing…

- Setting

- Does your main character live in a city? Start coming up with details on what it’s like. Do they live in a wilderness instead? Well, they’re probably familiar with their surrounding area to a point, so…

- Where does your story begin? A room, a meadow, a jail cell…? Know something about that place.

- etc.

Worldbuilding can get super granular, to the point of describing how your three moons affect tidal patterns, what foods, games, and songs people celebrate with for the Generic Fantasy Harvest Festival, and titles for the major books of the religion you created. In fact, if you want to see some epic fucking worldbuilding, check out The History of Middle Earth and discover what’s possible when you work on developing your world for most of your life.

Eventually, that “World” category is going to split into more detailed categories, like technology, religion, geography, and so on. But at this point in the file, I haven’t thought of that stuff yet! I cannot emphasize enough that I do not plan. Like, at all. I come up with the basics, and start running. The rest comes later.

If you’d like to start your world with a stronger foundation…

- SFWA: Fantasy Worldbuilding Questions (really thorough)

- Medium: A Worldbuilding Checklist

- CRV’s D&D Reading Room: A World Building Checklist (don’t underestimate the skill of dungeon masters, is all I’m saying)

Do a Google search for “worldbuilding checklist” for more, although these–especially the SWFA link–should cover you.

Using Scrivener’s unique capabilities

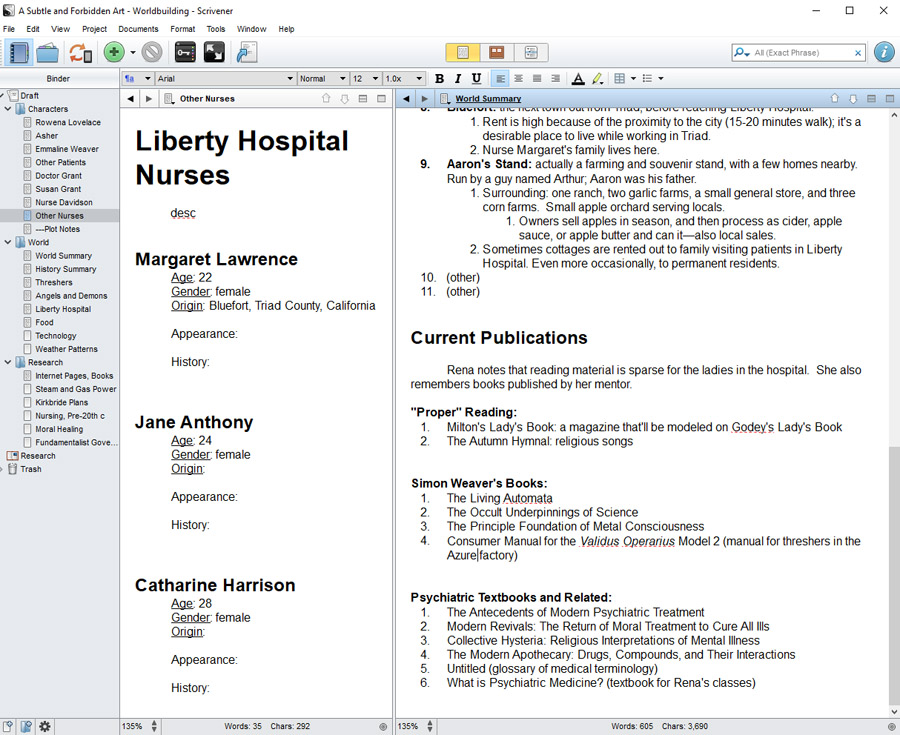

There are two especially useful features: the split screen, which I mentioned above, and the “import web page” feature.

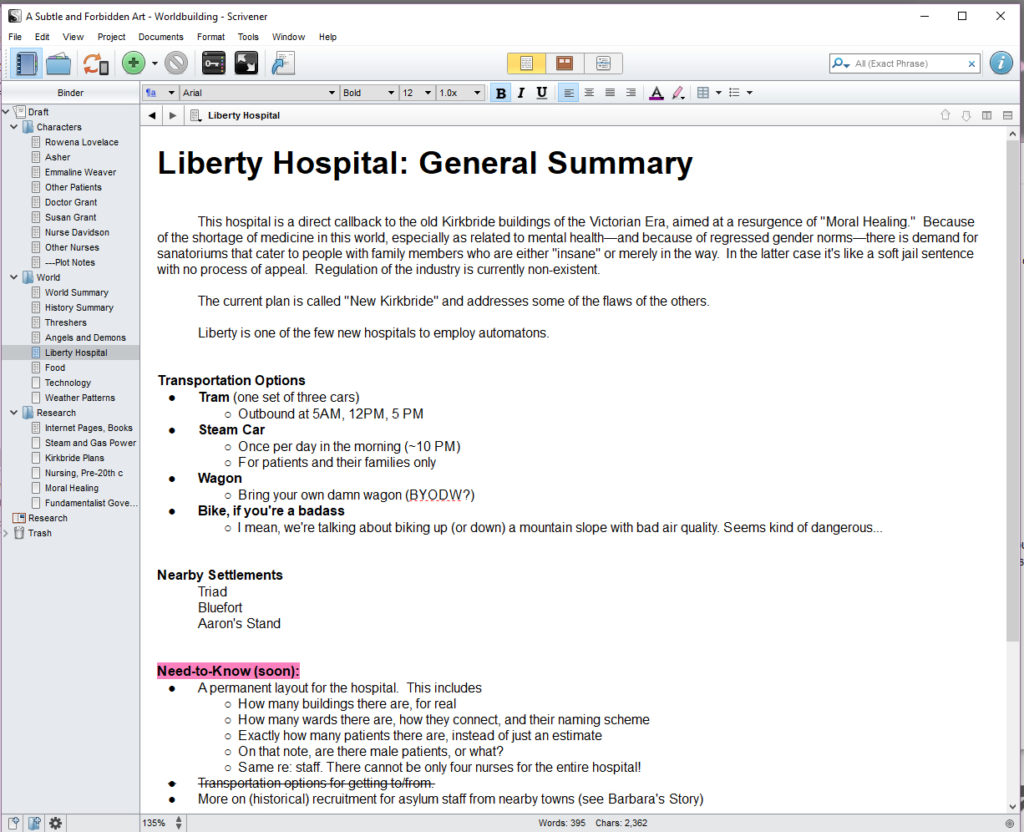

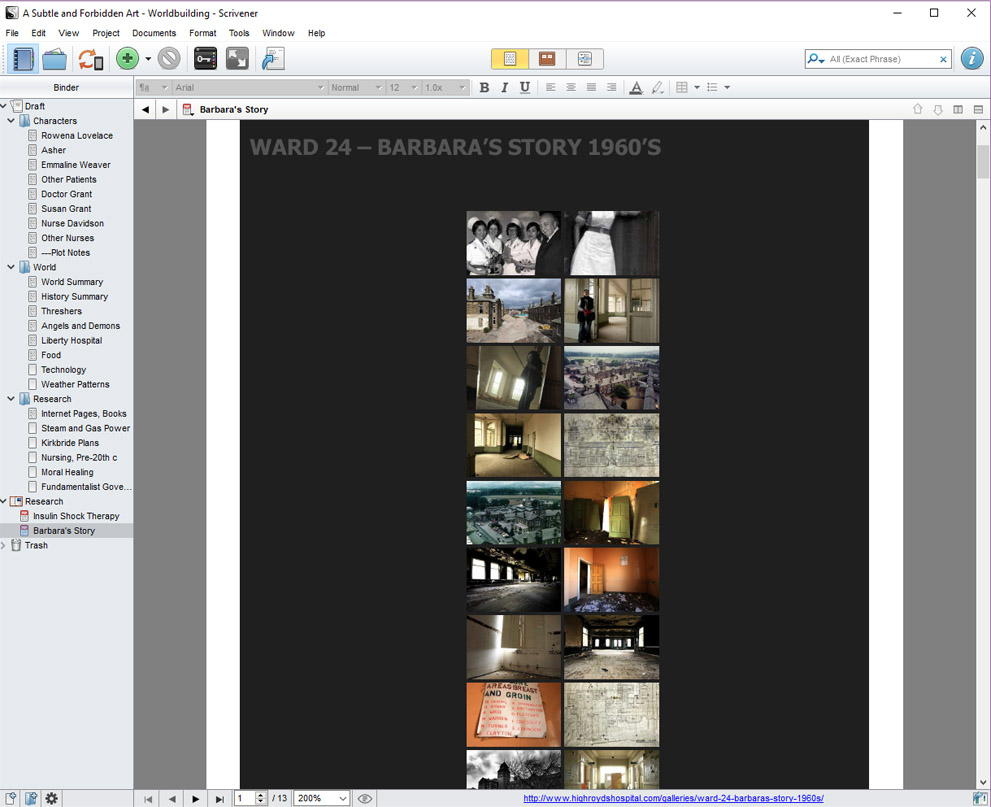

Below is my world-tracking file for this year’s Nanowrimo story, which is a bit more developed than the example project I made for this entry:

This is not amazingly complex (and I feel compelled to note that I’m going to change a lot of this), but hey, if you want to feel better about your own worldbuilding, here you go! This is my running note sheet of “shit I added to the story and should remember later, for the sake of consistency.” Because I have two monitors, I can keep Scrivener open on one side, and my story file on the other, so this file was incredibly convenient as-is. However, if you don’t have dual monitors, Scrivener’s got a fix for that: split screen!

This is also quite handy when you’re writing a scene later in the book, but need to refer back to earlier dialogue, description, or notes. Or, in my case, if you need to look at character profiles + some other information, like books they might read, or places they might have grown up. When Margaret said, in an actual scene, “I hated that Collective Hysteria book–it’s full of nonsense if you want to actually treat these conditions,” well, I had to go find that title again. I came up with it on November first, and had forgotten it by the fifteenth.

Scrivener has other capabilities that I tend not to use for worldbuilding, myself. The corkboard is great if you like to plot that way, but it’s not something I find useful. Templates, as I said, are also not my thing. But I realized recently that Scrivener can import webpages, which has the potential to be incredibly useful.

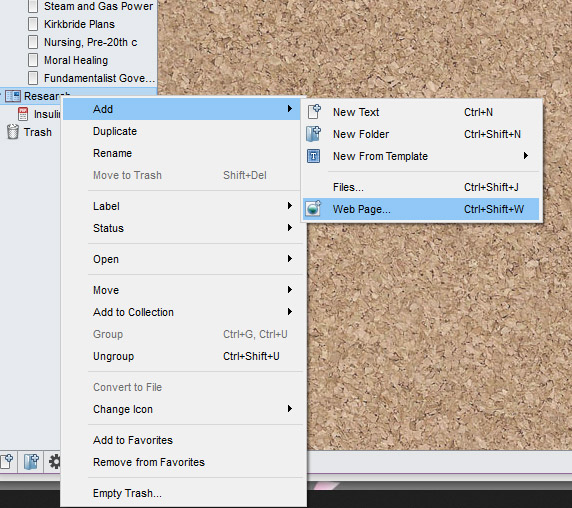

Note that, if you want to save a webpage with images, you will have to use the “Research” folder at the bottom of the list. Other areas of your project will preserve plain text only.

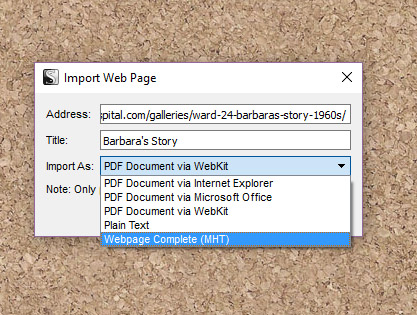

My Nanowrimo story took place in an asylum, and featured a few antiquated therapies I want to research for the next draft. Since you never know when a web page will disappear, I think it’d be a good idea to preserve the ones I have in mind. This means I’m going to right-click on the Research folder and add a page:

The next window will ask for the address, title, and which file type you want to use for your import.

Although I have the last option highlighted, I always default to the first option on the list: PDF Document via WebKit. Webpage Complete opens the content in a separate window, and I’ll have none of that, thanks.

Now Barbara’s Story is stored in my project as a PDF. It looks small, but you can adjust magnification to make it readable.

Concluding Notes

I know I’ve missed things that might be potentially useful. God only knows how long the program has allowed imports from the internet–maybe always?–and yet that slipped right past me! I can’t possibly be harnessing Scrivener’s full potential. So, that begs the question:

How do you use Scrivener? Share your secrets! What did I miss?

Very useful! I have bookmarked this post to come back to

I just stumbled upon this post and it’s AMAZING. I hope you’ve gotten far on your journey! Thank you for taking the time out to post all this information!